By KOICHI FURUYA/ Editorial Writer

December 1, 2022 at 19:02 JST

While Jiang Zemin gave the impression of being a grim politician in public, behind the scenes, he showed a more friendly side in meeting with reporters.

The former Chinese president died on Nov. 30 at 96.

In 1998 at Zhongnanhai, the secluded compound in central Beijing where the top-ranking officials of the Communist Party Central Committee work, Jiang met with a delegation from The Asahi Shimbun.

He said to me, “There are also young reporters here. Don’t you agree that young people have a brighter future?”

He displayed his unique sense of humor during the interview, using Japanese terms such as “arigato” (thank you).

When Jiang was asked who his favorite composers were, he replied, “Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann and also Mozart. It is better to have a wide range of interests.”

In 1997, Jiang visited the United States as president, the first state visit by a Chinese president in 12 years.

The interview with The Asahi Shimbun came at a time when he began developing confidence in his foreign affairs acumen.

After pro-democracy demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in 1989, Jiang was named general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party.

The most important task for the top Chinese leader of that time was to repair ties with the international community, which had plummeted to the lowest levels ever.

In steering a course to ensure the Chinese Communist Party remained in power even in a post-Cold War world, the Jiang administration chose cooperation with the international community and an open-door policy for the nation’s economy.

At the same time, it did not recognize political freedom and was dead set against democratization.

That created the twisted Chinese society that is still in place today.

Rapid economic development led to serious wealth disparity. To maintain the unifying force of the Chinese Communist Party that had lost its ideology amid the growing frustration among the populace over the wealth gap, Jiang chose to promote the strengthening of patriotic education.

The narrow-minded nationalism that ensued triggered anti-Japanese sentiment among Chinese youth, which had a noticeable effect on Japan-China ties.

During his 1998 state visit to Japan, Jiang demonstrated that he held a strong stance on issues related to the history between the two nations.

Even after stepping down as general secretary in 2002, Jiang continued to cling to power. While he stepped aside as general secretary and Chinese president and allowed Hu Jintao to take over, Jiang did not leave his post as the top leader of the military until 2004.

After retiring from politics, Jiang continued to maintain an office at Zhongnanhai and made suggestions regarding high-level appointments.

That inability to remain above the fray likely did not go over well with the Chinese population.

That continued involvement may have accounted for Jiang’s failure to gain the charismatic appeal held by past Chinese leaders such as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, even though he was the leader under whom China produced incredible economic gains.

Jiang was the leader who fostered both the light and shadow in China produced by the nation’s rapid economic development path.

***

Koichi Furuya was assigned four times as an Asahi Shimbun correspondent in China, including as the head of the China General Bureau in Beijing.

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

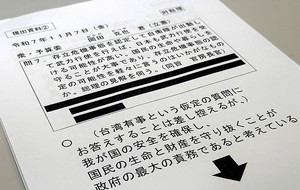

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II