By HAYASHI YANAGAWA/ Staff Writer

December 15, 2025 at 16:45 JST

HIROSHIMA—A family here has achieved closure over the death of a loved one killed 80 years ago in the atomic bombing through strands of a girl’s hair kept over the decades and DNA analysis.

Kanagawa Dental University identified a 13-year-old girl who died on Aug. 6, 1945, in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as Hatsue Kajiyama, who stayed behind after her family relocated to Manchuria.

Shuji Kajiyama, 60, Hatsue’s nephew, had sought the testing of the remains in the city’s possession and misidentified as belonging to Hatsue’s sister.

Hiroshima city officials contacted Shuji on Dec. 13 with the confirmation.

“I am glad I decided to undertake the DNA analysis, which was a major decision because I held concerns about the possibility that there might not be a match,” he said. “I hope other families in the same situation as us will have the remains of loved ones returned to them.”

REMAINED BEHIND BECAUSE OF SCHOOL

The Kajiyama family manufactured and sold rice cakes in the city, but with their lives facing greater difficulty, Hatsue’s parents and siblings moved to Manchuria in the spring of 1945.

Hatsue asked to remain in Hiroshima with her grandmother, Haru, because she wanted to continue studying at what was then a senior high school for girls.

Hatsue would often send letters to her parents and siblings in Manchuria, saying how she was studying hard so that she would score high on an upcoming test and be able to proudly face her family. She once complained that she had to stop studying due to the approach of enemy planes.

A second-year senior high school student, Hatsue and her classmates were called out from their school on Aug. 6 to help tear down a building to create a fire control zone and limit damage from U.S. fire bombings.

The students were about 1 kilometer from ground zero when the atomic bomb detonated, killing all 360 or so first- and second-year students, except for one survivor.

Hatsue’s grandmother was also killed by the atomic bomb as she worked in another area to create a fire control zone.

The Kajiyama family returned from Manchuria to Hiroshima the following year and searched in vain for Hatsue and Haru.

A major turning point came in 2021. According to Hiroshima city officials, one of the 70,000 or so remains that were not identified but kept within the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park was determined to be those of Haru.

While the kanji characters were different, a roster of those remains kept at the site had a listing for a Haru Kajiyama.

The key point was the location written on an envelope that had been stored along with the remains.

Kajiyama, Haru’s great-grandson, began wondering if the remains of another individual with the same kanji surname used erroneously for his grandmother might be Hatsue, his aunt.

The personal name for those remains was Michiko, Hatsue’s younger sister. It might have been possible that on that fateful day, Hatsue wore clothing or had possessions with her younger sister’s name written on it, leading to the mistaken identification.

When Shuji inquired with the Hiroshima city government in May, the address was the same location where Hatsue lived at the time.

HAIR SAMPLE PROVIDED DNA

The Hiroshima city government has not conducted DNA analysis for cremated remains even if asked by bereaved family members on grounds it was difficult to extract a sample. But this time, a few strands of hair were also stored in the remains container.

Shuji asked the city government to conduct an analysis.

City officials consulted with Kanagawa Dental University, which has conducted DNA analysis to help identify the war dead in the past.

The hair sample was taken to the university on Nov. 27 and DNA analysis was conducted by Hiroshi Ohira, 65, an associate professor of dental forensics.

On Dec. 10, Ohira succeeded in extracting DNA from the hair sample. It was compared with DNA taken from Michiko Daimon, 91, Hatsue’s younger sister, and no incongruities about a blood relationship were found.

It was the first time Kanagawa Dental University conducted DNA analysis on the hair of the war dead.

“The hair was stored in good condition and still had some luster,” Ohira said. “Keeping it in the container that sealed it from the outer air likely helped.”

FAMILY LIVED WITH REGRET AFTER BOMBING

Michiko told Shuji that Hatsue was diligent in her studies and was a dependable eldest daughter.

Hatsue’s mother, Takiko, always expressed regret at not insisting that she come with the rest of the family to live in Manchuria.

Shuji’s father shed tears when informed that his mother had been identified, but he died in 2023 not knowing about the remains of his older sister Hatsue.

Shuji is preparing to accept Hatsue’s remains early next year.

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

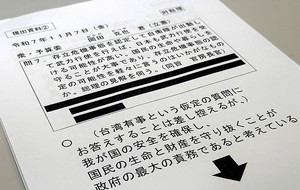

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II