By YO SATO/ Staff Writer

April 11, 2025 at 07:00 JST

TOYOOKA, Hyogo Prefecture—Health care experts around Japan are increasingly prescribing “community ties” instead of medicine to improve the health and well-being of residents.

The practice, called “social prescribing,” is a care model that connects people to community services and activities.

One place that promotes social prescribing is Daikai Bunko, a community library about 10-minute walk from JR Toyooka Station in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture.

Officially called, “A place with books and life: Daikai Bunko library,” it also serves as a book cafe.

It is operated by Yoichi Morimoto, a physician who works mainly for a public health center.

Morimoto, 31, who is also head director of “Care to Kurashi no Henshu-sha” (Care and living editing company), a general incorporated association, set up the community library in December 2020.

Through books, Daikai Bunko is intended to create an atmosphere that makes everyone feel free to enter, thereby serving as a “hangout” for residents of the community.

It also has functions that allow people to seek advice from health care experts on diseases, loneliness, isolation and other problems.

Workers refer advice seekers to social resources both within and outside the community library.

Morimoto said Daikai Bunko has so far been used by about 19,000 people. More than 1,000 have used its “hangout counseling office” stationed by health care experts.

More than 200 advice seekers have been “prescribed” to visit entities including “Daikai university for everybody,” where anyone is entitled to teach classes, and cafes in the neighborhood.

One man in his 40s with a mental disease said he began coming regularly to Daikai Bunko after he used its “hangout counseling office” functions.

Once a volunteer at the community library, he now prepares coffee and talks to Daikai Bunko users.

He has also taught a class at “Daikai university for everybody” on a subject that he is strong in. He said he is now living in good health.

Since attending Jichi Medical University as a student, Morimoto has been taking part in a movement of medical workers to become active in the neighborhood community.

Through the experience, he learned about an activity where medical workers pulled a food cart and distributed coffee to people.

Inspired, Morimoto in 2016 started “Yatai Cafe” (Food cart cafe), a similar project, in Toyooka, close to where he lives. He later decided to set up Daikai Bunko as a permanent activity base.

“Through neighborhood communities, we have forged ties with people who had been left out in the gap between existing frameworks,” Morimoto said. “The essential thing for us is to always be available to people. That prompts various things to spring up.”

LOCAL GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

The central government has also set its sights on social prescribing.

In its annual Basic Policies on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, more commonly known as the “big-boned policies,” from 2020 through 2023, the central government said it will promote social prescribing, including as a measure against loneliness and isolation.

The health ministry is conducting model projects on social prescribing in several areas.

Locally, the city of Yabu, Hyogo Prefecture, has set up a “social prescribing promotion division,” a rarity in Japan, to work on forging community ties.

The city of Nabari, Mie Prefecture, also promotes social prescribing.

Three staff members, including Toshiko Fukuma, work for a “community health office” in Nabari’s Mihata district as part of the endeavor.

Residents can make reservations for a “chat” through the website for the city’s community health offices.

“People from community circles sometimes come to us and say, ‘I just came to say ‘hello’ to you,’” Fukuma, 72, said. “If people come to us while they are fine and healthy, that makes it easier for us to deal with them when something goes wrong.”

She said she and her colleagues refer advice seekers to community circles and other entities as the need arises.

Nabari authorities set up 15 community health offices in the city between fiscal 2005 and fiscal 2007. They have a total of 30 workers who provide counseling on various subjects for all ages.

Yuya Mizutani, a physical therapist with the Hashimoto general clinic in Nabari, has been practicing social prescribing with the city’s community health offices.

Mizutani, 39, is a “link worker” whose duty is to connect isolated individuals with neighborhood communities.

He has been putting much effort into a community activity group called Chiichikaken, whose name carries the meaning “power and health for the community.”

Chiichikaken has set up a “gardening club” for patients and residents, who meet once a month to tend to the clinic’s garden and engage in other activities.

Chiichikaken organized a “class for making wreaths and doing physical exercise at a library” on Christmas Eve last year, and about 30 people participated.

Medical associations have also entered the picture.

In 2019, the Utsunomiya Medical Association in the capital of Tochigi Prefecture set up a “social support” section to promote social prescribing.

The section has compiled a database of groups that can support patients.

“As things stand now, doctors are saving patients downstream in the metaphor of a river,” said Tatsuro Katayama, a 67-year-old physician who headed the UMA when it established the social support section. “What we have to do, however, is address the social backgrounds of patients that lie farther upstream, such as loneliness and isolation.”

TIES SHOULD NOT BE FORCED

Tomohiro Nishi, a physician who leads the Japanese Social Prescribing Laboratory, said he believes that social prescribing does not, by any means, call for eliminating loneliness and isolation.

He said the goal of social subscribing is to create a society where people can stay lonely with a sense of security.

“Forcibly connecting those who wish to be alone would be ‘abusive social subscribing,’” Nishi, who is also head director of Plus Care, a general incorporated association, said. “We will have to look at the personalities, histories and backgrounds of individuals when we decide what we should do with them.”

Social prescribing was first recommended by the British health department in 2006.

The concept is about ensuring the involvement of workers from different domains, such as health care, welfare, education and community activity, to address “social determinants of health” that surround patients, such as poverty and loneliness.

Social subscribing is also drawing attention as a measure for dealing with the weakening of neighborhood communities due to the increase in one-person households and elderly people living alone.

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

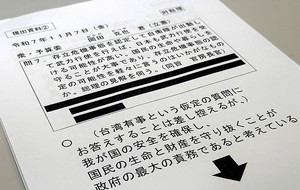

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II