March 20, 2025 at 14:54 JST

Sickened passengers are treated outside the Tsukiji subway station in Tokyo after a sarin gas attack on March 20, 1995. (Asahi Shimbun file photo)

Sickened passengers are treated outside the Tsukiji subway station in Tokyo after a sarin gas attack on March 20, 1995. (Asahi Shimbun file photo)

We cannot forget the day in 1995 when a terrorist attack in the nation’s capital abruptly and tragically shattered so many lives.

March 20 marks the 30th anniversary of the sarin nerve gas attack by the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult. This indiscriminate act of mass murder, in which 14 people were killed and more than 6,000 injured by the poison released in trains of three subway lines in central Tokyo, shocked the world.

What was particularly chilling was that most of the perpetrators were young people who had once been diligent, earnest students.

It remains crucial to grapple with the profound questions raised by this attack. Why were these individuals drawn to the cult, and how did they become capable of such a heinous crime?

MULTIFACETED INVESTIGATION IS ESSENTIAL

The terror attack, along with the Great Hanshin Earthquake that struck Kobe and its vicinity about two months earlier, prompted significant changes in society.

In response, the government established a crisis management center in the prime minister’s office.

Amid public debate over fundamental human rights, such as freedom of religion and freedom of association, the law regulating subversive organizations was enacted. This law granted authorities the power to conduct on-site inspections of organizations that had committed acts of indiscriminate mass murder.

Despite early warning signs, such as the sarin gas attack in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, in 1994, the police failed to conduct forced searches of the religious organization and were slow to act on these ominous indications.

Law enforcement authorities faced mounting pressure to reassess their approach to large-scale investigations.

Following the subway attack, police were criticized for making numerous arrests based on unrelated charges.

The high-profile actions of senior cult members, who repeatedly appeared on television after the attack, ultimately served as propaganda for the organization. This raised serious questions about the media’s approach to covering the cult.

Regrettably, despite the profound social implications of the incident, neither the government nor the Diet made sufficient efforts to thoroughly investigate and analyze the facts.

The death sentences of 13 former cult leaders, including Aum Shinrikyo founder Chizuo Matsumoto (also known as Shoko Asahara), were carried out in 2018.

Throughout his trial, Matsumoto remained largely silent, and it cannot be said that the true reasons why his disciples resorted to manufacturing and dispersing nerve gas have been fully revealed.

Few of the former senior cult members involved in the attack fit the typical image of a brutal criminal.

Among them were a former medical student with a medical license, a former University of Tokyo student who specialized in particle physics, and a former Waseda University graduate student who studied applied physics.

To fully understand the scope of these crimes, it is crucial to continue a multifaceted investigation involving experts from various fields, including religion, social psychology and counter-terrorism.

CULT’S RECRUITMENT PERSISTS

Last month, Senshu University students organized a forum to discuss lessons learned from the cult’s crimes. The generation born after the incident shared their research findings and engaged in meaningful discussions.

A male third-year student from Tamagawa University, who aspires to become a teacher, emphasized, “The subway sarin attack is not just a historical event; its effects are still felt today.”

Another student highlighted that victims continue to suffer from aftereffects. “We don’t know when we might be targeted by the cult’s recruitment efforts or impacted by its activities,” the student said. “It’s crucial to remain aware of potential risks and to pass these lessons on to future generations.”

According to the Public Security Intelligence Agency, even after the cult lost its religious corporation status, its followers continued to operate under successor and splinter groups like Aleph, Hikari no Wa (Circle of rainbow light) and Yamadara no Shudan (Yamada’s group).

These groups have 30 base facilities in 15 prefectures, with around 1,600 followers active in Japan. They recruit members through seemingly innocuous programs like yoga circles. Many new followers are in their teens and 20s.

Understanding how the past connects to the present is a crucial step toward applying the lessons learned.

Last month, the agency published a “digital archive” on its website, documenting issues related to Aum Shinrikyo. To create this archive, agency staff spent a year collecting photos, videos and victim testimonies.

One poignant testimony comes from Shinichi Ishimatsu, president of St. Luke’s International Hospital, who treated 640 victims of the sarin attack on March 20, 1995.

In his account, he describes the immense challenges the hospital faced in caring for the patients.

Shizue Takahashi, who lost her husband in the attack, opened a website titled “Memory of the Subway Sarin ‘Terror’ Incident.”

The power of firsthand records is undeniable. Relevant ministries must continue to preserve and publicly share vital information to ensure the incident is never forgotten.

To expedite relief, victims recently asked the justice minister to direct the government to purchase and recover about 1 billion yen in compensation debt that Aleph is obligated to pay.

As the victims continue to age, this request serves as an opportunity to reflect on measures that should be taken to support those who were innocently caught up in such a tragic event.

NO SIMPLE ANSWERS

At the time of the attack, Japan was trying to deal with the collapse of its asset-inflated bubble economy. Although the social climate may have changed, baseless conspiracy theories continue to circulate, and extreme viewpoints still hold influence.

The atmosphere of uncertainty and vulnerability of today closely mirrors the environment that led many young people to be drawn into Aum Shinrikyo.

The rise of the internet has made the spread of various ideologies more accessible, increasing the risks of encountering cults and self-righteous, dangerous thoughts.

Ikuo Hayashi, the only perpetrator of the sarin attack who avoided the death penalty and instead received a life sentence, reflected on his mindset before joining the cult in his book “Aum to Watashi” (Aum and me).

“There must be a law that solves problems that modern science has avoided or cannot solve,” he wrote.

It is often said that when people face insurmountable challenges, they tend to retreat into a simplistic worldview. Everyone experiences moments of being lost on the path to self-realization, when the desire to escape from the harshness of reality becomes overwhelming.

Cults exploit this vulnerability, offering easy answers that draw people in. It is crucial not to convince oneself that “I’m fine,” but instead to seek guidance and support from those around you.

The grief of the victims’ families remains profound, and their physical and emotional wounds continue to endure.

We must preserve the memory of this horrifying event by passing it on to future generations, and persistently reflect on it so that such a tragedy is never repeated.

--The Asahi Shimbun, March 20

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

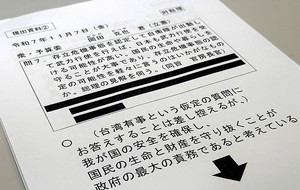

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II