By AKIHITO OGAWA/ Staff Writer

April 14, 2025 at 18:30 JST

The once-accessible process of designing a custom home is turning into a luxury option as Japan's carpenters join the growing number of industries suffering a shortage of trained professionals.

The trade's workforce has dwindled to a third of its former size over the past 40 years, sparking concerns over rising housing costs and stalled home renovations.

“We can’t find any carpenters” is a growing complaint heard by CraftBank Inc., a subcontractor platform that organizes events to match carpenters with housing developers.

At these events, company representatives are lining up in front of carpenters to exchange business cards with them.

“I'm turning down jobs left and right,” said a 30-year-old contractor who employs two people in the Kanto region, which includes Tokyo.

Despite sometimes being offered barely profitable terms, he maintains a strong negotiating position and said the old hierarchy where subcontractors were seen as inferior is fading.

Thanks to a thriving business, his after-tax income exceeds 10 million yen ($69,000) annually.

According to the national census, the number of carpenters peaked at 930,000 in 1980. By 2020, it had fallen below 300,000, with projections indicating a possible drop to 150,000 by 2035.

The land ministry also notes that new housing starts declined by 35 percent over a 15-year period ending in fiscal 2020. The carpentry workforce shrank even faster with a 45-percent dip.

This imbalance is driving up costs. Kei Tamura from home inspection firm Sakura Jimusho Inc. said that custom homes will increasingly be seen as a luxury commodity.

In Tokyo and the surrounding areas, the average price of a custom-built home reached 54.66 million yen in fiscal 2023—nearly double that of 2013. Rising labor costs may push prices even higher.

According to Nomura Research Institute Ltd., demand for home renovations is expected to increase modestly, driven by aging homes and the rising prices of new construction projects.

The growing carpenter shortage could also delay crucial projects such as seismic retrofitting, something that has raised safety concerns.

PUSH FOR LABOR REFORM

Kenji Takagi, director of CraftBank Soken, attributes the shortage to long-standing labor practices.

To reduce corporate social benefit expenses, contractors have increasingly outsourced projects to independent carpenters rather than hiring them as formal employees.

These practices became widespread after Japan’s asset bubble collapsed in the early 1990s, giving rise to a multi-layered subcontracting system that stalled improvements in working conditions.

“The old model of outsourcing cheaply without investing in training is what created today’s shortage,” Takagi said.

Additionally, vocational schools that once trained young carpenters are disappearing. Without better pay and stability, younger generations are avoiding the trade altogether, leaving behind an aging workforce.

Still, some companies are pushing for change.

Major homebuilder Sekisui House Ltd. significantly ramped up its hiring of full-time carpenters, adding 134 new employees in April 2024—3.4 times more than the previous year.

Tokyo-based Momoyama Construction Co. has hired six staff carpenters since 2017 and, in addition to their standard bonus, provides them with a year-end bonus of 100,000 yen to purchase new tools.

“Hiring workers as permanent employees is standard in other industries,” said Kenichi Kawagishi, who is Momoyama Construction's executive director. “As they develop their skills as carpenters, they can deliver higher-quality work that better meets their customers’ needs.”

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

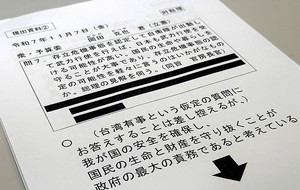

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II