By SHINICHI IKEDA/ Staff Writer

December 19, 2024 at 07:00 JST

Takashi Mikuriya (Photo by Reina Kitamura)

Takashi Mikuriya (Photo by Reina Kitamura)

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party and its junior coalition partner, Komeito, lost a combined majority of seats in the Oct. 27 Lower House election.

That, however, did not lead to a change of government. LDP President Shigeru Ishiba won a runoff to remain at the helm of Japan as prime minister.

In a recent interview with The Asahi Shimbun, political scientist Takashi Mikuriya shared his thoughts on what phase the Japanese politics is in as the country is soon to mark 80 years from the end of World War II.

Mikuriya is well-versed in the history of Japanese politics from the Meiji Era (1868-1912) onward. He is also on intimate terms with politicians in both the ruling and opposition blocs.

Excerpts from the interview follow:

***

Question: A minority Cabinet of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is starting, as the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition has lost the majority of seats (in the Lower House) for the first time since it lost power and went into opposition in 2009. What historical significance does that have?

Mikuriya: Perhaps something is going to happen that cannot be captured in the time frame of the first time in just 15 years.

I cannot help thinking that Japanese politics has entered the time of the biggest change since the LDP was founded in 1955 through a merger of two major conservative parties, the Liberal Party (1950-1955) and the Japan Democratic Party (1954-1955).

We should not take a cynical view and say things of the sort, “The Ishiba administration will be short-lived,” or “The Democratic Party for the People will end up buried in the gap between the ruling and opposition blocs.”

We should see this as an opportunity for a creative change in Japanese politics that has arrived for the first time in quite a long while.

Q: Do you mean the “1955 system,” wherein the LDP holds sway, is being shaken?

A: Yes. The 1955 system has lasted so long that politicians, bureaucrats, scholars and journalists alike tend to think of it as a given premise, but it is, in fact, not a condition that never changes. We should look upon the situation in the belief that what is going to begin now is a process of creation for a new political method, order and system.

Actually, the LDP had never experienced, since it was founded, being in a minority government, which it is in now. The party fell from power and went into opposition twice (in 1993-1994 and 2009-2012), but in all other periods, the LDP maintained a majority in the Lower House (either alone or with coalition partners) as it administered the government.

It has therefore been the practice for nearly seven decades that important decisions are made in advance within the ruling party or the ruling coalition, which manages its relations with the opposition parties by adjusting schedules through unofficial negotiations among members of the Diet Affairs Committees of the parties concerned.

Nobody has ever experienced a tense Diet situation where a vote of no-confidence in the Cabinet could be passed at any moment.

BACKROOM DEALING NO LONGER WORKS

Q: The LDP got through previous crises by forming coalitions with other parties. What is different now from situations in the past?

A: I think the situation is altogether different.

In 1983, former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka (1918-1993) was sentenced to prison (at the first trial) for his involvement in the Lockheed payoff scandal. The LDP fell from the majority in a Lower House election that soon followed, and the Cabinet of then Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone (1918-2019) formed a coalition with the New Liberal Club (1976-1986).

That ended a long spell of the LDP’s single-party administration and marked the first time it had ever formed a coalition.

After the LDP suffered a crushing defeat in the 1998 Upper House election, it entered a coalition in 1999, under the Cabinet of then Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi (1937-2000), with the Liberal Party (1998-2003) led by Ichiro Ozawa. Later in that year, Komeito joined the coalition, in which it remains today.

A political scene that evokes the 1955 system, however, has persisted to this day.

Let me explain where the difference is this time around.

The LDP formed coalitions, at previous times of emergency, with parties led by former LDP members, namely Yohei Kono (of the New Liberal Club) and Ozawa.

Insider communications among those who had been in the LDP, such as switching between public and backroom dealings and sending out unspoken messages, therefore worked with those partners.

If I may dare to add a few words, the presence of the New Party Sakigake (1993-1998), founded by Masayoshi Takemura (1934-2022), Shusei Tanaka and other politicians who had left the LDP, played a key role when the LDP formed a (tripartite) coalition with the Social Democratic Party of Japan and Sakigake from 1994 through 1998 to retake power.

By contrast, the DPP, whose help the LDP is soliciting now, is a group of politicians, including the party head Yuichiro Tamaki, who have never been in the LDP in national politics. The party is therefore completely different from previous LDP partners.

The DPP is not even setting up a standing body for holding talks with the LDP. It likely wants to do everything openly. The DPP is also set to hold talks in the same manner with other opposition parties, including the (leading opposition) Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan.

Previous experiences in forming coalitions, and the thinking of the backroom policy dealing among Diet Affairs Committee members of the ruling and opposition parties, no longer work. I think the LDP is being terrified by this situation.

In fact, (former Prime Minister) Nobusuke Kishi (1896-1987), who was inaugural secretary-general of the LDP, in 1955 called on Inejiro Asanuma (1898-1960), head of the (leading opposition) Japan Socialist Party, to say there was a need to set new rules of parliamentary democracy in the months and years to come.

Asanuma was the first to serve as secretary-general (leader) of the JSP (predecessor of the SDP) after its right and left factions were reunified in 1955.

I think we have entered a stage, precisely now, for setting new rules to replace those that the bureaucratic organization, seated in Tokyo’s Kasumigaseki district, and the LDP have created since that time.

Q: Do you mean a task of such historic importance is on the shoulders of politicians today?

A: Yes. We cannot afford to pose as connoisseurs of the politics of Tokyo’s Nagatacho district (the seat of Japan’s national politics) to talk cynically and complain, for example, that “all politicians have become lightweight since the single-seat constituency electoral system was introduced (to the Lower House in 1994).”

Some of the relatively obscure and inexperienced politicians, who have had few opportunities to play active roles, could make a name for themselves.

History is really ironical.

Most of the LDP’s factions have disbanded after former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida abruptly released a plan (in January) to have his own faction dissolved. That has weakened the pressure of factions on individual politicians to an unprecedented level, even though Kishida probably never intended anything of the sort.

Politicians who have remained obscure within the LDP could therefore get around to doing a spectacular job, irrespective of seniority.

If it had not been for Kishida’s declaration of faction disbandment, Ishiba, a politician who is totally different in nature from previous LDP leaders, would simply never have made it to the prime minister’s seat, be it by a very slim margin.

ISHIBA’S VACILLATING STANCE

Q: You once likened Ishiba to a “missionary.” Could you elaborate?

A: I met him on multiple occasions and wrote character sketches of him twice about a decade ago.

One of Ishiba’s maternal great-grandfathers is Michitomo Kanamori (1857-1945), a Christian missionary of great interest who lived from the Edo Period (1603-1867) through the Showa Era (1926-1989). Ishiba is a fourth-generation Christian who was strongly influenced by him.

I believed, when Shinzo Abe (1954-2022) had unrivaled strength (as prime minister from 2012-2020), that Ishiba needed to evolve from a missionary into a man of action, but he ended up becoming prime minister while he still remains a missionary.

It’s not enough to say that Ishiba has a weak power base within the LDP. He practically has no power base whatsoever when compared to his predecessors as LDP president.

Things therefore don’t work out easily as he wishes. The timing of his (Lower House) dissolution alone is already different from what he had argued for earlier, and he was blamed for the inconsistency of his remarks. He will likely continue to vacillate in his stance.

And like a missionary, Ishiba continues to spin out words that tend to be taken, no matter what, as naive and glossed over. And he will continue to explain with that signature look: “Oh no, I am not being inconsistent, because ...”

The minority government already means that things don’t go as he wishes. The extent to which the public will accept the way he is will hold the key.

Ishiba is not a dashing and sophisticated figure of the sort that Morihiro Hosokawa was when he was prime minister (from 1993-1994). Ishiba is a typical Japanese man who appears very tired.

But he sort of embodies this country, which has remained in disarray for more than 30 years and has never stopped getting buried and losing ground on the international plane.

We will be watching, for the time being, how this person will represent Japan as its leader to meet other leaders of the world, including Donald Trump, who is returning to U.S. presidency.

CDP ON THIN ICE

Q: What will become of the CDP, the leading opposition party?

A: The latest election results have brought the CDP to the center of people’s hopes and attention for the first time in some while. The party is facing an extremely crucial phase, as it has won, for example, chairmanship of the Lower House Budget Committee despite its opposition status.

The CDP, however, obtained more seats than before not because it has acquired solid strength but simply because the LDP and Komeito waned. The party, in that sense, is treading on even thinner ice than the LDP is.

I appreciate the way that CDP officials did not overstretch themselves to try and take power, even though I have no idea if they understood the situation they are in or if they simply lacked the numbers and ability for doing so.

Even if they had used various means to take power on the latest occasion, things would evidently have gone awry for them, as they would have become stuck in a divided Diet, where the LDP-Komeito coalition commands a majority in the Upper House. CDP President Yoshihiko Noda, who experienced a failure in the past (as prime minister from 2011-2012), probably knows that.

I believe that CDP members know the crucial moment for creating a new political scene is about to begin ahead of the Upper House election next summer.

The Upper House election will be held at a time when the LDP-Komeito coalition is shy of the majority in the Lower House.

Not only the CDP but also all other opposition parties would fail to win the approval of the public in the Upper House election if they were to do nothing but to grill another party over scandals or oppose something.

The public would turn its back on the CDP if it were to rely on the logic of insiders to appoint people to positions to reward their services or only set forth policies that seldom win the hearts of the public.

The starting gun has been sounded for creating a new political order. The race is ready for all politicians.

Political scientist Yoshisato Oka (1921-1999) once said he believes that democracy is likely a form of politics that is “close to us.”

I think we have reached the precise moment when we face the test of whether politics will become something close to the public or something far removed from them.

There would be a crisis of Japan’s party politics and democracy if people were to believe that politicians are spending all their time only for pursuing party interests for taking power.

***

Born in 1951, Takashi Mikuriya, a scholar of the history of modern and current Japanese politics, is a professor emeritus with the University of Tokyo and a professor emeritus with Tokyo Metropolitan University.

He has written books including “Kenryoku no Yakata wo Aruku” (Strolling around mansions of power), “Nihon Seiji-shi Kogi” (Discourse on the history of Japanese politics) and “Heisei Fuunroku” (Records of the winds and clouds of the Heisei Era (1989-2019)).

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

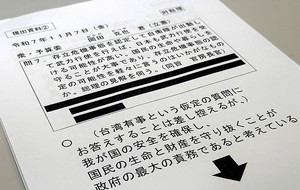

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II