November 5, 2024 at 13:46 JST

Yuichiro Tamaki, president of the opposition Democratic Party for the People, speaks after the Oct. 27 Lower House election. (Kazuhiro Nagashima)

Yuichiro Tamaki, president of the opposition Democratic Party for the People, speaks after the Oct. 27 Lower House election. (Kazuhiro Nagashima)

The debate over the Category 3 system of the National Pension, a public pension system all people with an address in Japan are required to enroll in, is gaining traction.

This system, created during an era when full-time homemakers were the majority and the nation’s workforce was plentiful, has also been criticized for hindering improvements in the compensation and benefits offered to female employees and women’s career development.

However, there are important issues that need to be carefully addressed before making the policy decision to abolish it. A detailed and meticulous examination of these issues is necessary.

The public pension system classifies enrollees into Category 1 for self-employed individuals and students; Category 2 for company employees and public servants; and Category 3 for dependents of Category 2 contributors, who can receive the national pension (basic pension) without paying premiums themselves.

The annual income threshold for no longer qualifying as a dependent and being required to pay social security premiums is 1.06 million yen ($6,900) for employees at workplaces with 51 employees or more and 1.3 million yen for others.

This has led to the phenomenon known as the "annual income wall," which encourages dependents doing part-time and other non-regular jobs to adjust their working hours to stay below these thresholds and remain exempted from social security contributions.

Last month, Rengo, or the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, the umbrella organization of labor unions, decided to push for the abolition of Category 3.

Rengo said it will launch a campaign to promote the proposal, calling for the step at national advisory councils and other opportunities.

During the Oct. 27 Lower House election, the Democratic Party for the People pledged to review the system, and Nippon Ishin (Japan Innovation Party) promised to consider abolishing Category 3 in its respective campaign platform.

The government plans to address the "annual income wall" issue by providing temporary subsidies that effectively cover the insurance premiums for Category 3 pension members whose income surpasses the threshold while simultaneously working on reforming the system.

Over the past 30 years, the number of Category 3 enrollees has decreased by about 5 million, dropping below 7 million, 40 percent of whom are employed.

Rengo aims to first change the system to ensure the “full application” of the employees' pension and health insurance to company employees, public servants and workers who are currently Category 3 pension members.

Until now, many businesses have preferred hiring Category 3 workers where possible to reduce labor costs, as this allows employers to avoid being required to cover half of the social insurance premiums for their employees, as in the case of regular employees.

However, amid labor shortages, a growing number of companies are willing to shoulder the premiums to retain employees for the long term. The benefits of working more to increase pension benefits in old age, even if they go beyond the “wall,” are beginning to be recognized by workers as well.

By addressing wage disparities between men and women and improving the work environment, and by expanding pension enrollment to include the entire workforce so that all workers pay insurance premiums based on income, even for short working hours, the "wall" can be eliminated.

Moving toward a system that is neutral to the way of working is a step in the right direction, and both ruling and opposition parties are coming to view this approach as an acceptable solution.

However, among Category 3 enrollees, there are "vulnerable Category 3" individuals who cannot work due to child care, caregiving, personal illness or unemployment.

For these people, the basic pension available through Category 3 has been an essential support for a minimum standard of living in old age.

Abolishing Category 3 without preparing a safety net for these vulnerable individuals and treating them the same as self-employed individuals to collect premiums from them would be unreasonable.

Ensuring reasonable final decisions on the scale, scope, and funding of the envisioned new safety net is crucial. A policy discourse that goes beyond slogans is needed.

--The Asahi Shimbun, Nov. 5

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

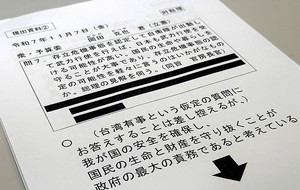

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II