By TAKAHIRO OGAWA/ Staff Writer

September 22, 2023 at 17:08 JST

After the start of discharging treated radioactive water into the ocean from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, a number of Japanese businesses received hundreds of crank calls from angry Chinese.

Four ramen restaurants in Fukushima Prefecture belonging to the same business group fielded about 1,000 such calls, forcing workers at those eateries to temporarily disconnect their phones.

The writer’s mother is Chinese and his father is Japanese. The animosity between Japanese and Chinese over the discharge of the treated water by plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Co. has been a stressful experience.

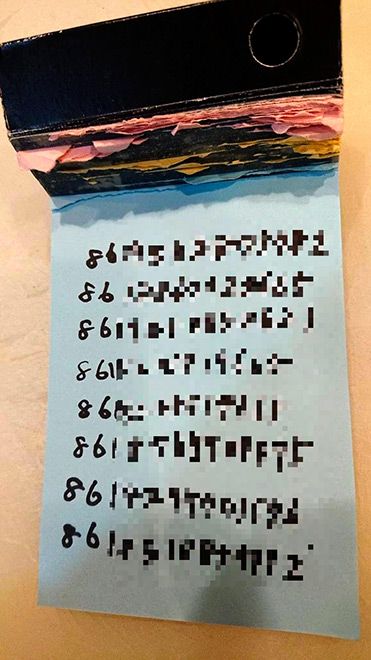

To learn what drove Chinese to make such calls, the writer received the phone numbers of those who placed the anonymous nuisance calls from the Fukushima ramen shop that had jotted some of them down.

On the first call to one such phone number, an angry voice screamed, “So what if I made a crank call to Fukushima? I have no intention of being interviewed, you idiot!”

Contact was made using WeChat, a Chinese social messaging app, but the first response was, “We Chinese hate the Japanese. There is no point to interviewing me.”

After several more messages were exchanged, the Chinese male placed a call through a smartphone.

“I hated Japan from elementary school mainly due to issues related to the history between the two nations,” he said. “This is the first time in my life I have spoken with a Japanese.”

The caller explained that he was 18 and lived near the ocean in northern China. After graduating from senior high school, he has been working rather than continuing on to higher education.

Six days earlier, he called the Fukushima ramen shop to protest the discharge of treated radioactive water.

He said he saw news reports about many Japanese supporting the decision to start the discharge.

“I saw over the internet someone placing a call to the number so I decided to make a call myself,” he said.

He wanted to find out directly why Japanese supported the decision to release the water.

“I placed one call to the Fukushima shop on Aug. 24 when the water release started,” the teenager said. “When the call went through, the person who picked up the phone began speaking in Japanese and I couldn’t say anything. The connection was cut off.”

When the caller was informed that the shop’s group had received about 1,000 crank calls in total, he said, “I never realized the situation had reached such a stage.”

The phone conversation lasted about 30 minutes. The writer told the Chinese teenager that while there may be many anti-Chinese posts on the internet in Japan, there were also many Japanese who did not feel that way.

The caller replied, “I will not likely change my hatred of Japan. But I am glad to have spoken with you. If I get another opportunity to talk to a Japanese in a situation other than a crank call, I hope to speak without having a preconceived notion based on my initial impression.”

After the phone call, the teenager sent a message that said, “Mah-jongg is also popular in Japan, isn’t it?” He attached a video of himself happily playing the traditional tile game.

The writer sent a reply: “I look forward to the day when I can play mah-jongg with you.”

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II