By YOKO HASEGAWA/ Staff Writer

August 14, 2023 at 07:00 JST

Leading apparel makers are expanding their mending services as they become more aware of sustainability amid growing calls for such services.

Noriko Saiki, a senior manager at the Japan Research Institute, who is well-versed in the relationship between fashion and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, cites a change in consumer behavior for the increased popularity of mending services.

“The negative environmental impacts of the fashion industry became widely known, prompting eco-friendly ethical consumption behaviors to rapidly become widespread among them,” she said. “There is a new view among consumers, too, that it’s cool to upcycle favorite clothes and wear them longer.”

Since olden days, it has been common in Japan to fix and remake kimono to wear the traditional clothing for a long time.

But Saiki said the recent wave of repairing and recycling is not just nostalgia but a new way of enjoying fashion, adding that the movement will further expand.

However, retailers are facing a labor shortage as they try to keep up with the rising trend.

REDUCING WASTE

Fast-fashion retailer Uniqlo Co. opened a Re.Uniqlo Studio inside its Setagaya-Chitosedai outlet in Tokyo in October 2022.

Specializing in repairing and remaking its own products, the shop-in-a-shop studio fixes tears, adds embroidery to old clothing and provides other alteration services for a fee.

“It seems to satisfy the needs of customers and it has been well-received,” a publicist said.

The Re.Uniqlo Studio permanently operates at three Uniqlo shops in Japan, accepting many orders to fix puffer jackets and the damaged crotch area of jeans, for example.

After launching the service at a store in Germany, Uniqlo has also opened the mending studio at 24 outlets in 13 countries and regions, including Britain and Singapore.

The brand intends to further expand the service at home and abroad.

An estimated 15,000 tons of clothing were repaired in Japan in 2009, according to a report released by the Environment Ministry in 2021.

That rose to 110,000 tons in 2020.

Similar efforts are also being made outside Japan.

For example, the French government has announced it will subsidize clothing and shoe repairs to reduce waste starting in October, according to local reports.

Spain’s Inditex, which operates the Zara clothing outlets, launched a mending service for its products in Britain in November 2022.

Meanwhile, an outdoor brand whose products are usually used in extreme natural environments has been taking the lead among such makers in offering mending services.

Patagonia Inc.’s Japanese arm operates two repair centers in Kanagawa Prefecture, mending 20,000 articles of clothing each year.

Mark Little, who oversees product planning at its U.S. headquarters, explained that when he plans to make a product, he gives serious thought to whether it even needs to be made and whether consumers will want it.

He always keeps repairs in mind from the designing stage, using easier-to-fix regular buttons instead of snap buttons and opting for durable materials.

Little added that he makes sure to create products that last a lifetime and that he wants to change the consumption cycle where things are bought and thrown away.

GROWING NEEDS, DECREASING LABOR

While there is a growing need for such services, the clothing industry is faced with a labor shortage.

“The number of repair shops has been decreasing faster than that of sewing shops over the past decade,” said Hidekazu Sato, head of the repair department at the Japan Apparel Quality Center. “With such artisans aging and there being fewer of them, some places are unable to handle the number of orders they used to manage.”

The center, which had become independent from Onward Group’s quality control division, founded the Shibaura Repair Workshop in May last year to provide such services for corporate customers.

It mainly receives alteration orders from textile trading firms that wholesale products to apparel makers, while it also fixes clothing damaged during the production process to make it sellable.

The center also started accepting orders from individual customers about six months ago.

Sato said there is a strong need.

“Those who ask for a difficult fix are also good customers who cherish their clothes and buy a lot of clothing,” he said.

Young people have shied away from working as repair workers because the job requires time and discipline while paying low wages.

The studio, where about 20 employees work, is trying to train young workers.

“It is the kind of job that requires steady work and it takes time to see your efforts bear fruit. Some people can’t stand it and quit,” said Akiko Isai, 64, who teaches name embroidering and other techniques to younger staffers.

Sato added: “We want to pass the techniques down to the next generation, even if only little by little.”

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

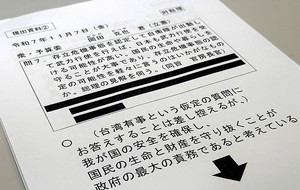

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II