By YOSHIKO SATO/ Staff Writer

January 13, 2025 at 18:58 JST

KYOTO—Excitement filled the air at Imakumanokannonji temple in Kyoto’s Higashiyama Ward when four “maiko” (apprentice geisha) appeared on stage, wearing white makeup and sporting traditional hairstyles with seasonal flower hair pins.

Their sashes swayed as they walked up to greet the 120-or-so photographers who had signed up in advance to attend the event.

Toyokazu Kosugi, secretary-general of the Kansai Headquarters of the All-Japan Association of Photographic Societies, which organized the Nov. 29 event, had a strict rule for the photographers.

“Maiko have the ‘right of publicity,’” he told the participants. “Please refrain from using (the pictures) for commercial purposes.”

He and the association had even tougher rules for non-participants and foreign tourists who were preparing their smartphones.

“This is a paid photo session,” they were told. “No photos allowed.”

The event, called “Gion’s Maiko photo session,” underscored a movement aimed at halting the unauthorized commercial use of images of “geiko” (geisha) and maiko, and to protect their economic benefits and value in Kyoto’s entertainment quarters known as “kagai.”

The participation fee for the photo session was 5,000 yen ($32) for members of the All-Japan Association of Photographic Societies, and 11,500 yen for non-members.

The “right of publicity” in Japan refers to the protection of the economic benefits derived from an individual’s personal appearance or name, including stage name.

For example, people can have economic value if they have the “power to attract customers” by virtue of their celebrity and good image.

If a third party uses that “power” and receives benefits without gaining permission or compensating the person, the individual’s right has been violated.

Such rights are not limited to celebrities. News reports and biographies that use such power of the individuals are not considered a violation of the right of publicity.

This right of publicity, however, is not explicitly stated in law. The term was mentioned for the first time in 2012 in a Supreme Court decision.

The term and concept of right of publicity were unfamiliar to the Kyoto’s kagai communities until recently.

One reason it became a hot topic was a large billboard advertisement displayed on a Shinkansen platform at JR Kyoto Station.

The advertisement was placed by Somi Shokuhin Co., a Kyoto-based producer and seller of various seasonings. The company has been using geiko and maiko from Gion Kobu, one of the five major kagai traditional entertainment districts of Kyoto, as models for its advertisements since 2018.

However, a customer at a teahouse in a kagai district who saw the billboard asked the proprietress, “Do you get paid (for the billboard advertising)?”

It was the first time the proprietress heard about the right of publicity.

She looked around the city and found many cases of “suspected infringement of rights.” In one souvenir store, postcards featuring pictures of maiko from decades ago were being sold.

Until now, organizers of photo sessions and movie and commercials shoots using geiko and maiko provided a “flower fee,” which is equivalent to a daily allowance, and a “congratulatory money gift.”

However, there was no remuneration for the finished work.

Kyoko Sugiura, chair of the Kyoto Kagai Kumiai Rengokai association, said, “Kagai is built on the association with patrons.”

She recalled, “There was an atmosphere of uncertainty as to whether it was appropriate to bring in the secular world’s order.”

The heads of Kyoto’s five major kagai districts also became aware of the issue.

“Geiko and maiko are not models in beautiful kimono but the embodiment of Japanese culture itself,” they said. “Considering the future generation of geiko and maiko, we must protect the kagai culture by guaranteeing their economic benefits and social status.”

Starting in spring 2023, these leaders spent more than six months discussing the issue.

As a result, they decided that those who want to film geiko and maiko would be asked to submit an application form that would include information on how the recordings would be used, when and for how long they would be made public, and the scope of their use.

The leaders also decided that a separate “license agreement” would be exchanged for commercial use of the images.

Somi Shokuhin, the company that advertises on the billboard at JR Kyoto Station, signed an agreement in February 2024.

The contract was backdated to November 2023, and Somi Shokuhin will pay compensation based on the agreement on top of the flower fees and other funds it had previously paid.

“As the rules of traditional culture are gradually changing with the times, (the company) received a request from the kagai district regarding the right of publicity,” Yuki Yamada, president of the company, said. “As a business headquartered in Kyoto, I believe that responding to the request will help protect traditional culture.”

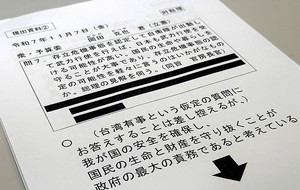

A document outlining measures to protect the rights of geiko and maiko was distributed to teahouses in the five kagai districts that serve as contact points for filming requests.

Yukiko Sumida, who runs the Imasa teahouse in Gion Kobu, said she has been concerned that an increasing number of people with no association to the kagai community were taking pictures in the neighborhood without permission.

“I did not know what to do, but now that we have a countermeasure plan, I am glad that the kagai community can warn people. This is an initiative that originated in Kyoto, but I hope it will spread to other kagai districts throughout the country,” Sumida said.

In recent years, people in the kagai community have been troubled by cases in which inappropriately taken images spread quickly on social networking sites.

In some cases, sneak photographs of geiko and maiko walking around in ordinary clothes have appeared on social media.

There are growing hopes in the kagai community that the movement will serve as a deterrent to such acts.

Yoichiro Komatsu, a lawyer who chaired the Intellectual Property Lawyers Network Japan, said, “Protecting the rights of publicity and portrait, which are recognized by the Supreme Court, as the rights of geiko and maiko should take root as a common practice.”

Regarding the act of posting pictures of geiko and maiko on social media without the consent of the subject, Komatsu said: “Even if the person uploading on social networking sites thinks he or she is transmitting culture, what they are doing is against the law. It is an extremely important step to keep an eye out for geiko and maiko in order to protect them.”

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II