By EIICHI MIYASHIRO/ Senior Staff Writer

January 16, 2025 at 08:00 JST

Fossilized bones discovered decades ago and hailed at the time as the oldest human remains found in Japan turn out to be from a prehistoric bear, a new analysis shows.

Not only that, the items are not nearly as old as researchers once thought they were.

The stunning about-turn was announced by academics primarily from the University of Tokyo and Niigata University of Health and Welfare.

It followed an exhaustive study of arm and leg bones that constitute the Ushikawa remains unearthed from Toyohashi, Aichi Prefecture, in the 1950s.

The new finding by Gen Suwa, a specially appointed professor of anthropology at the University Museum of the University of Tokyo, and his colleagues has been published in the bulletin of the Anthropological Society of Nippon.

The Ushikawa remains were found in 1957 at a quarry in the Ushikawa-cho district of Toyohashi.

They were initially pronounced as dating to the Middle Pleistocene (781,000 to 126,000 years ago) and recorded as such in textbooks on the history of Japan.

But by the 1980s, researchers had become skeptical about the age of the Ushikawa remains and whether they were even human.

With the help of Aiko Saso, an assistant professor of anthropology at Niigata University of Health and Welfare, the research team subjected the fossils to microscopic analysis and CT scanning.

Fragments that were formerly believed to be pieces of the humerus and femur were compared with bones from 24 black and brown bears.

Examining the depth of a hollow in the femoral head, the shape of the epiphysis and other elements, the team concluded they are “all bear remains.”

The study also revealed that the Ushikawa remains are younger than previously estimated.

The fossils were determined to date back more than 20,000 years, based on animal finds nearby after the Ushikawa discovery.

Given the local distribution of large mammals during the Late Pleistocene (126,000 to 11,700 years ago), the team said the Ushikawa remains are most likely those of a brown bear.

Other sites that were once thought to have yielded significant human remains from the distant past include the Mikkabi remains in Hamamatsu, the Kuzuu remains in Sano, Tochigi Prefecture, and the Akashi remains in Akashi, Hyogo Prefecture.

With advances in dating technology, those discoveries have been re-examined and many of them are found to be either from much later periods or not human at all.

The Ushikawa finding means that the Hamakita remains from Hamamatsu--estimated to be 17,000 to 22,000 years old with dating technology--are the sole known human remains from the Old Stone Age (12,000 years ago or earlier) outside the southwestern Nansei Islands of Okinawa Prefecture.

A peek through the music industry’s curtain at the producers who harnessed social media to help their idols go global.

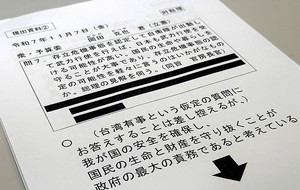

A series based on diplomatic documents declassified by Japan’s Foreign Ministry

Here is a collection of first-hand accounts by “hibakusha” atomic bomb survivors.

Cooking experts, chefs and others involved in the field of food introduce their special recipes intertwined with their paths in life.

A series about Japanese-Americans and their memories of World War II